Public Opening Friday, November 8, 2024 6 - 8 PM

125 Newbury proudly presents Irwin/Bell: The 1960s, an exhibition that juxtaposes two key protagonists of the Los Angeles art scene of the 1960s: Robert Irwin and Larry Bell. Comprising seminal works made during the artists’ legendary time living and working in Venice, California, the exhibition tracks Irwin’s and Bell’s radically individual yet closely related pursuits into the possibilities of extending perception. The works in Irwin/Bell trace an aesthetic shift on the part of both artists—a move away from illusionism and toward a new art of concrete reality—which laid the groundwork for each artist’s most significant contributions.

Robert Irwin, Untitled, 1967

Curated by Arne Glimcher, Irwin/Bell: The 1960s takes us back to a moment of LA art’s uneasy arrival in New York during the 1960s. It was during that decade that both Irwin and Bell presented their first New York solo exhibitions at the Pace Gallery on 57th Street. In 1965, Bell debuted his newest sculptures made from vacuum-coated glass cubes on clear Plexiglas pedestals. Irwin’s first New York show—which featured his “Dot paintings”—opened at Pace the following year. Up to that point, both artists had exhibited almost exclusively in Los Angeles—mostly with the Ferus Gallery. In 1967, Bell would present a second exhibition with Arne, and in 1968, Irwin premiered his aluminum disc paintings at Pace. Each time, Arne worked closely with the artists to design the installations and prepare the space, which was carefully calibrated to provide a pristine and neutral context for the work.

Grounded in the shared history and aesthetic investments of these two pioneering artists, the exhibition encompasses key works from Bell’s early glass sculpture in juxtaposition with important examples from several of Robert Irwin’s most celebrated series, including the line paintings, the discs, and the columns. All works in the exhibition date to the 1960s. A major highlight is one of Irwin’s most accomplished aluminum discs, debuted at Pace in 1968. This is shown alongside two of Irwin’s best line paintings, both of which were first exhibited at Ferus in May of 1962. A reviewer writing of Irwin’s new paintings that same year interpreted the work as a shift away from an earlier, abstract expressionist mode of picture-making, what the writer called “action painting,” and toward a new emphasis on “contemplation.”

This contemplative approach would become a hallmark of Irwin’s career, but it also grew to be endemic of the sensibility that would define the Light and Space movement. The iconic glass boxes and walls that Larry Bell began creating in the mid-1960s call for a similarly contemplative mode of viewing. Bell, who had been Irwin’s student at the Chouinard Art Institute in the late 1950s, absorbed and evolved Irwin’s ideas in radically new ways. His glass cubes transmogrify the illusionistic geometries of his earlier paintings into something physical, materializing them from pictorial space into three-dimensional presence, which coalesces around the physical fact of the glass object yet seem to dissolve the borders of the object at the same time. Bell’s boxes manipulate and distort volumetric space almost alchemically, transforming our perception through effects of reflection, luminescence, and atmosphere.

Larry Bell, Untitled, 1966-1967

Unlike Irwin’s emphatically hand-made paintings, which depended in part on their imperfections, Bell’s cubes are the result of a pristine technological production process. Bell utilized a vacuum chamber to interrupt the molecular surface of the work itself, producing the semitranslucent and reflective surface in the form a thin layer of particles deposited like a film onto the glass and fused into it. Like Irwin’s acrylic column from roughly the same period, Bell’s boxes become a trap for the real—like gravitational disruptions in the fabric of space-time, warping our experience of the surrounding room. Through the resulting compression and isolation of space—bending time along with reflection and optical density—Bell’s cubes mobilize Irwin’s lessons, altering our perception of the very fabric of reality.

Although Irwin and Bell are seen today as exemplars of the Light and Space movement in California, the exhibition nuances this complicated history, exploring how their works embodied two very different approaches to a shared set of concerns. Bell’s hyper slick, technologically sophisticated sculpture traversed different territory from Irwin’s more fugitive and conditional mode of artmaking. As their careers progressed beyond the Sixties, the gap between their practices widened. During the crucial decade of the 1960s, however, their concerns—and their art—were closely aligned. Both artists confronted the heady question of how to push the boundaries of art itself to create a new kind of experience for the viewer, one that would offer a wholesale expansion of our powers of sensory perception.

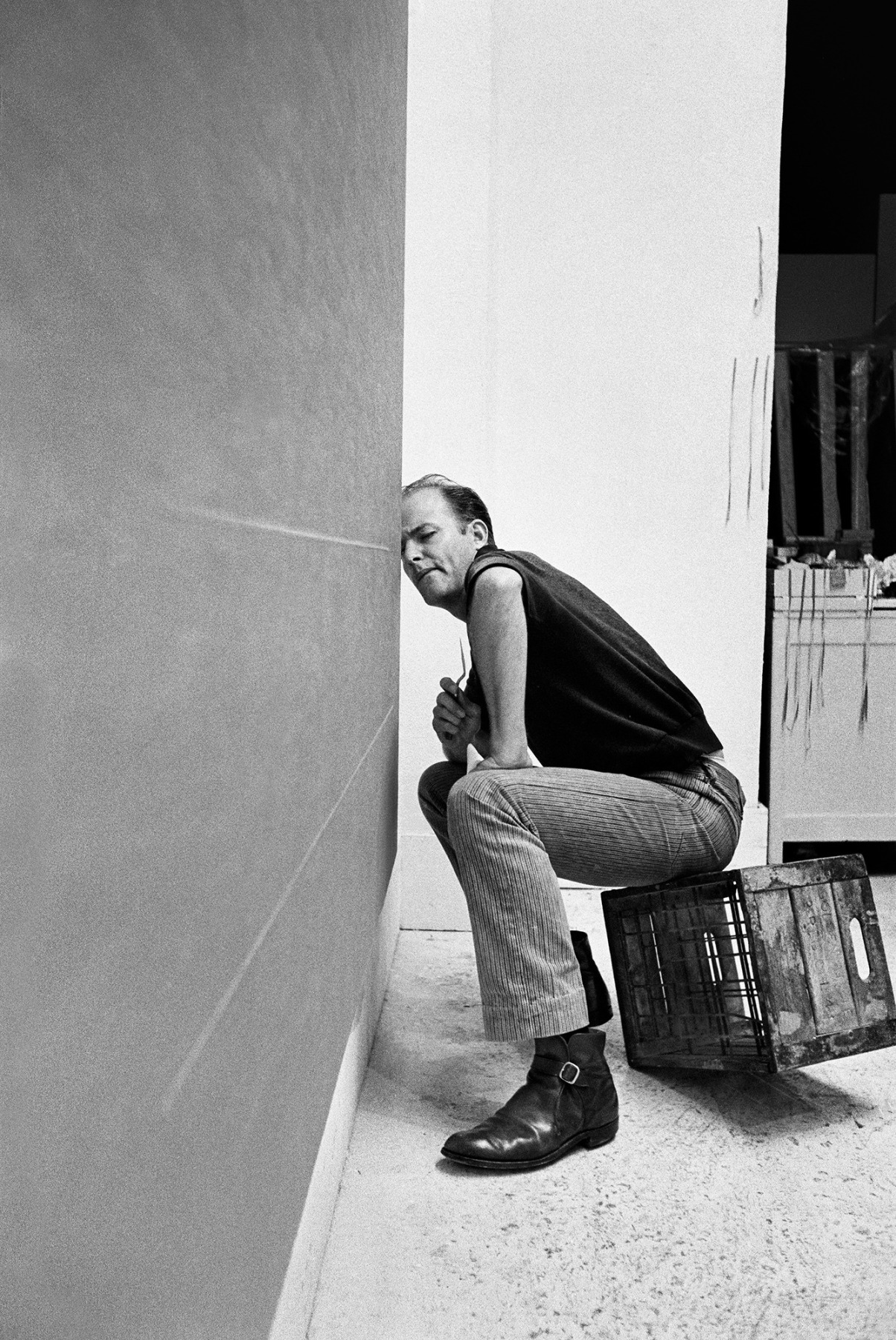

Robert Irwin's studio, Venice, California, 1962 Photo: ©Marvin Silver

Robert Irwin (b. 1928, Long Beach, California; d. 2023, La Jolla, California) was a pioneering figure of the Los Angeles-based Light and Space movement of the 1960s. Beginning his career as a painter, Irwin later began exploring perception and light with his acrylic columns and discs. In 1969, he gave up his studio and began what he termed a conditional practice, working with the effects of light through subtle interventions in space and architecture. Irwin employed a wide range of media—including fluorescent lights, fabric scrims, colored and tinted gels, paint, wire, acrylic, and glass—in the creation of site-conditioned works that respond to the context of their specific environments.

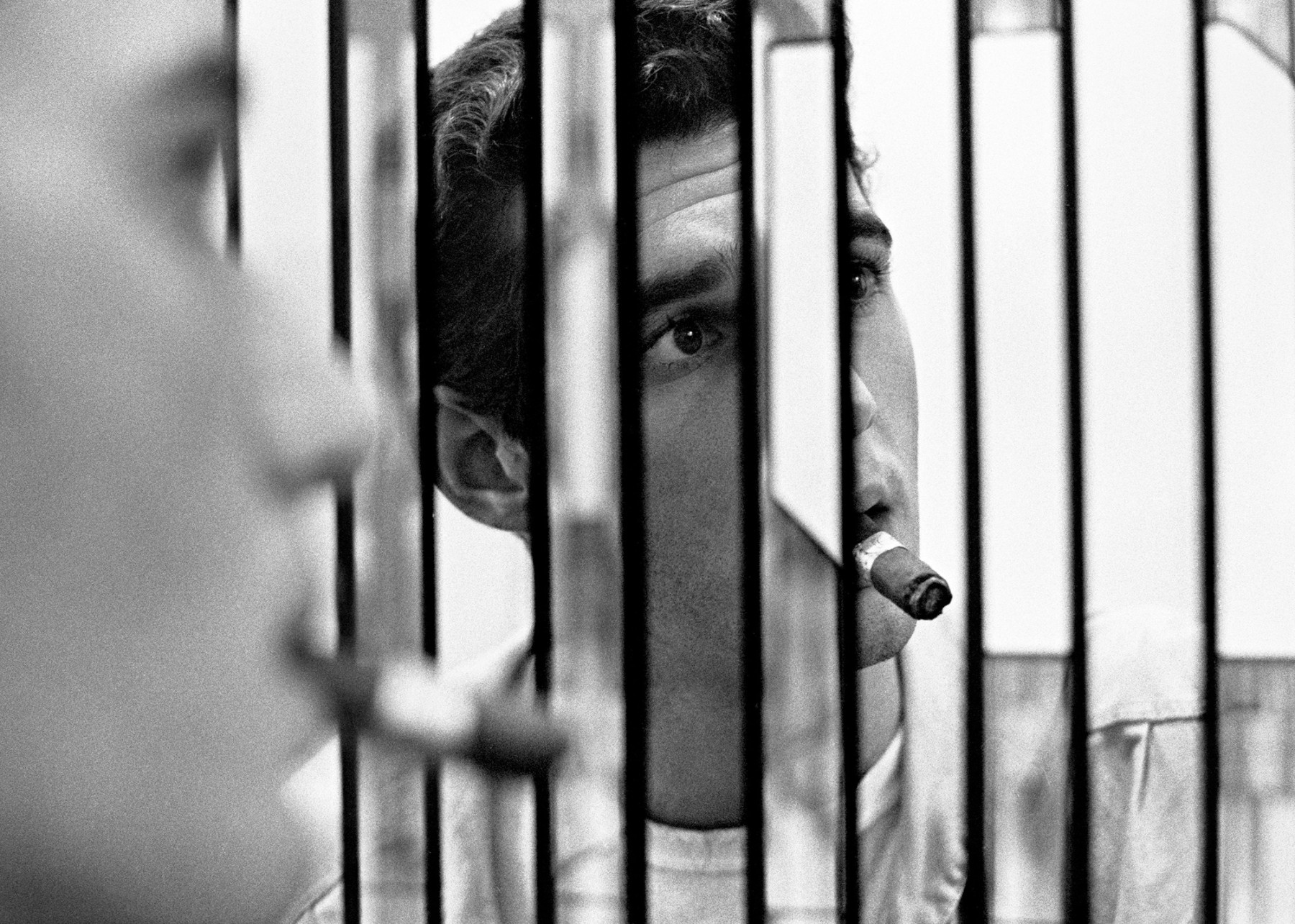

Larry Bell’s studio, Venice, California, 1963 Photo: ©Marvin Silver

Larry Bell (b.1939, Chicago, Illinois) is one of the most renowned and influential artists to emerge from the Los Angeles art scene of the 1960s, alongside contemporaries Ed Ruscha and Robert Irwin. Known foremost for his refined surface treatment of glass and explorations of light, reflection, and shadow through the material, Bell’s significant oeuvre extends from painting and works on paper to glass sculptures and furniture design. Bell began his career in 1959 with abstract paintings and shaped canvases resembling boxes. Panes of glass and mirrors were substituted for parts of the painted design, and this exploration of spatial ambiguity eventually evolved into sculptural constructions made of wood and glass. This evolved into wood and glass sculptures. From 1963 onward, Bell focused on light and used a method called vacuum deposition to add thin films to clear glass in his cube sculptures. These cubes, displayed on clear pedestals, captured light and created unique patterns—challenging notions of mass, volume, and gravity in one single measure.